The perspectives of young people on hard work, benefit fraud, and interpersonal trust are the subjects of a recent study by the Näringslivets Skolforum — the forum of the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, a major employers’ organization in Sweden.

Authored by Nima Sanandaji, the study gathers some relevant data about attitudes towards work across different nationalities and age groups. One of the key findings is that the weakness of diligence as a societal norm in Sweden may be limiting the country’s ability to cultivate and retain valuable skills within its workforce. The analysis is primarily based on a review of data collected by the World Value Survey since the early 1980s.

Do Swedes value diligence?

Diligence, or hard work, is widely recognized as crucial for students’ academic success. However, a question in PISA — an international assessment that evaluates the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students, conducted every three years by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — reveals that the norm of diligence is weak in Swedish schools. PISA 2008 examined how many students feel satisfaction with working as hard as they can. In Sweden, just under six out of ten students reported doing so, the second lowest proportion after Finland.

The strongest values in this regard were held by students in South Korea, where 92% stated that they feel satisfaction in working as hard as they can.

The study notes that a significant challenge in Sweden is that many who study engineering, for example, do not complete their studies. While the coursework is demanding, the high dropout rate suggests that the school system may not adequately train students in the diligence required to succeed in the future. Promoting perseverance in school — so that more people do well in their studies — could lead to Sweden being more successful in developing skilled professionals in the future.

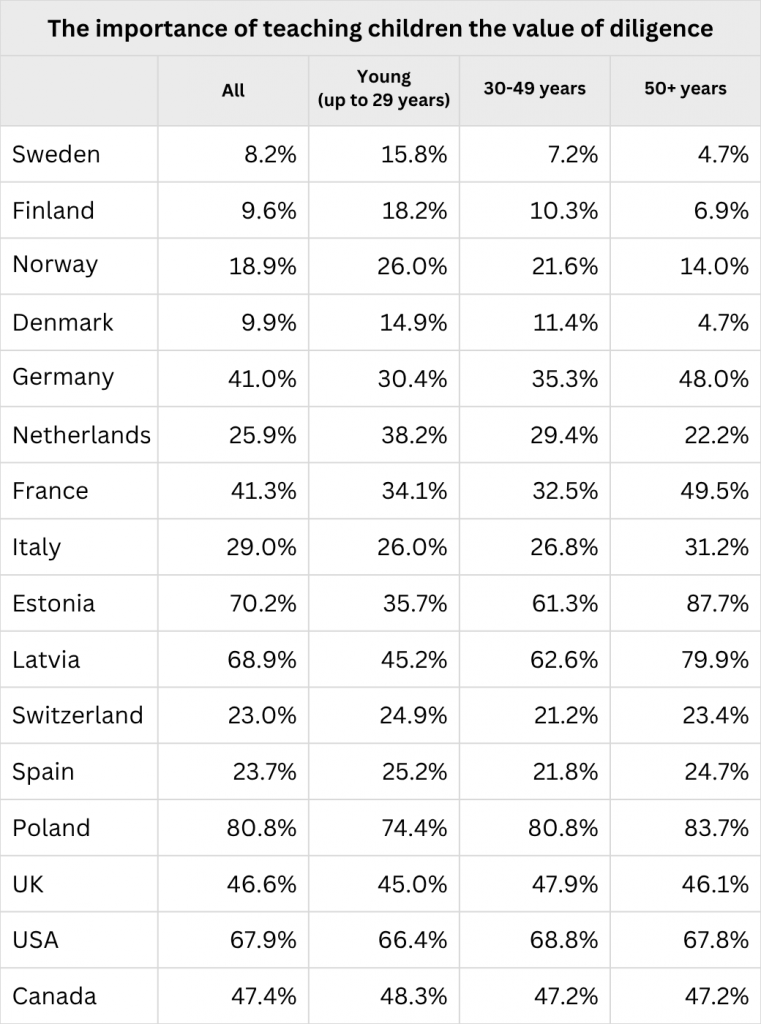

In the World Value Survey, participants were given a list of qualities that can be encouraged in children at home and asked which quality, if any, they considered particularly important, with a maximum of five responses allowed. “Hard work” was one of the answer options.

Among young people in Sweden (up to 29 years old), few emphasize the importance of teaching children diligence, with only 15.8% doing so (the share among older people is even lower). In Denmark, the proportion among young people is even slightly lower: 14.9%. In Norway, however, the corresponding proportion is 26%, and in Germany, 30.4%. In the United States, 66.4% of young people believe it is important to teach children diligence.

The study inquires whether the tax ratio is a valid explanation for the data presented above. It references Jean-Baptiste Michau’s research, which explores the connection between public spending and the intergenerational transmission of work norms. Michau noted that parents make rational choices in raising their children, based on expectations about the policies that will affect the next generation. More generous welfare states reduce the incentives to strengthen work norms in children, as high taxes and generous public benefits reduce the benefits of effort.

If the analysis is limited to individuals born in Sweden, only 6.8% of the general public identifies diligence as an important characteristic. In contrast, among the population as a whole, the proportion rises to 8.2%. This data indicates that the value placed on diligence is stronger among foreign-born individuals in Sweden.

Attitudes toward idleness

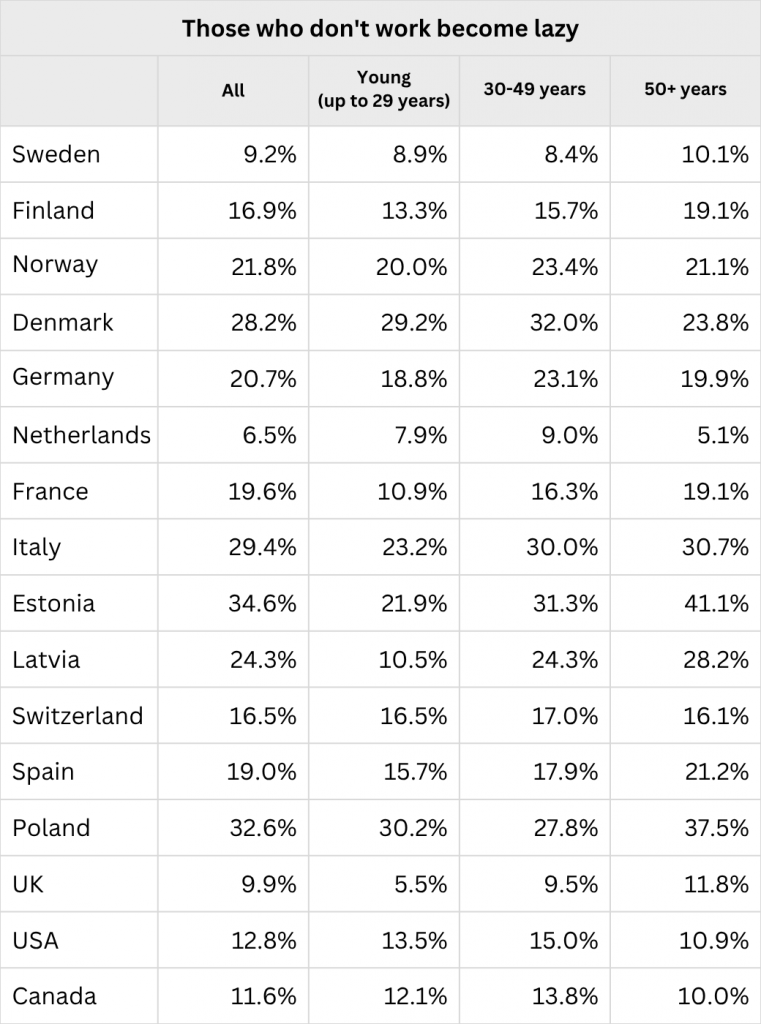

Another question asked by the World Value Survey is whether those who do not work become lazy. In Sweden, 8.9% of young people strongly agree that those who do not work become lazy, compared with 13.3% in Finland, 20% in Norway, and 29.2% in Denmark. In the UK and the Netherlands, the proportion is even lower (5.5% and 7.9%, respectively).

Norms against passivity are stronger among foreign-born people in Sweden: in the Swedish population as a whole, 9.2% strongly agree that those who do not work become lazy, compared to 7.9% among native-born people. Like the diligence norm, norms against passivity are, therefore, stronger among foreign-born Swedes than among native-born Swedes.

The ethics of benefit use

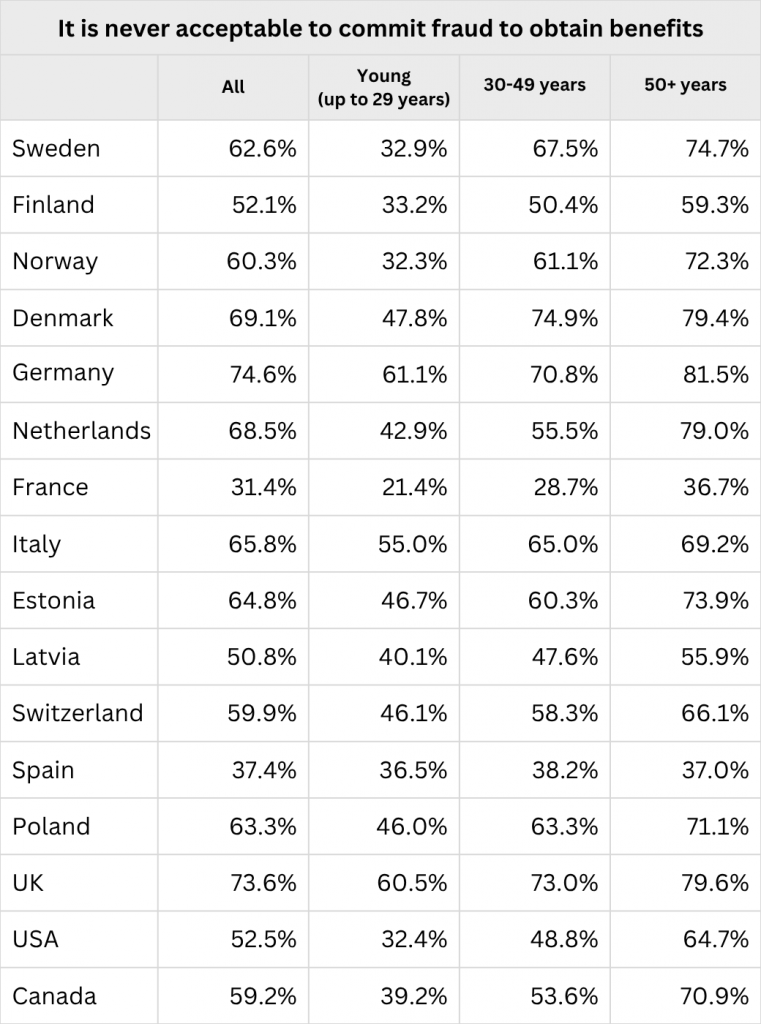

Acceptance of benefit fraud in Sweden has decreased since the beginning of the 2010s, but is still high compared to the situation in the 1980s.

In the early 1980s, 46% of young people in Sweden agreed that it is never acceptable to receive public benefits to which one is not entitled. By the beginning of the 2010s, this proportion had decreased to 27%. The societal norms against benefit fraud have been somewhat strengthened recently: in the latest surveys, 32.9% of young people in Sweden believe that benefit fraud is never justified.

There are notable generational differences in this matter in Sweden. Among individuals aged 30 to 49, 67.5% believe it is never acceptable to receive public benefits one is not entitled to. This belief is even stronger among older individuals (aged 50 and above), with 74.7% agreeing.

Sweden is among the countries where the lowest proportion of young people agree that benefit fraud can never be justified. Over half of young people in Germany (61.1%), Italy (55%), and the UK (60.5%) think that benefit fraud is never acceptable.

Work in the future

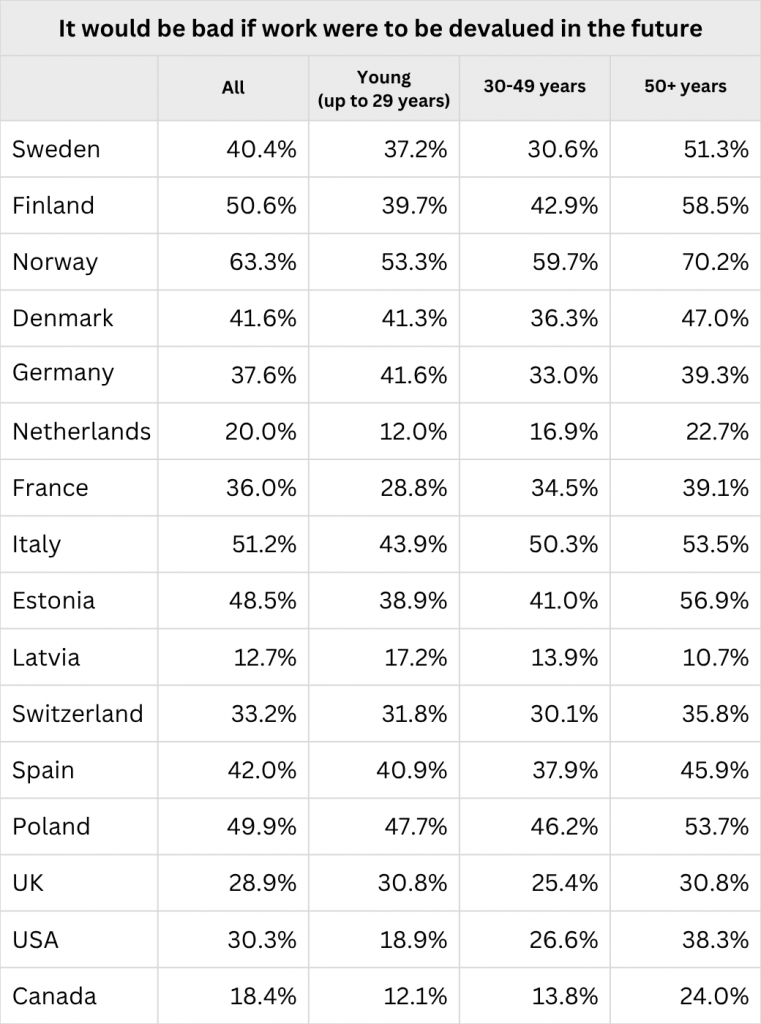

One of the questions in the World Value Survey is whether it would be good or bad if we placed less importance on work in the future than we do today. In Sweden, 37.2% of young people believe that it would be unfortunate if we placed less importance on work in the future. This is a relatively high figure, which can be compared with the situation in the USA (18.9%), Latvia (17.2%), Canada (12.1%) and the Netherlands (12%).

Sweden is similar to the other Nordic countries in this matter. In Finland, 39.7% of young people believe it would be unfortunate if society placed less importance on work in the future. In Denmark, this figure rises to 41.3%, while in Norway, an even higher 53.3% of young people feel the same way. This trend is not limited to the younger generation; it applies to all age groups.

The study lists a few possible explanations for this Nordic trend, including the awareness that the comprehensive welfare systems provided by high-tax countries like Sweden are expensive and must be financed through hard work — both in the future and today.

Swedes’ trust: high but declining

The level of trust we have in others is something we develop during childhood, and it usually remains relatively stable throughout our lives. The author points out that trust norms are passed down through generations.

The study references a report by the Nordic Council of Ministers, which calls trust the hidden gold of the Nordics, as it fosters collaboration and innovation. Societies characterized by high trust require fewer formalities and are better at resolving conflicts and avoiding legal disputes. Additionally, European countries with higher levels of trust tend to have a higher proportion of innovative companies. The study highlights that trust also encourages investment. Therefore, trust emerges as a societal norm that is strongly linked to the innovative strength of Nordic economies.

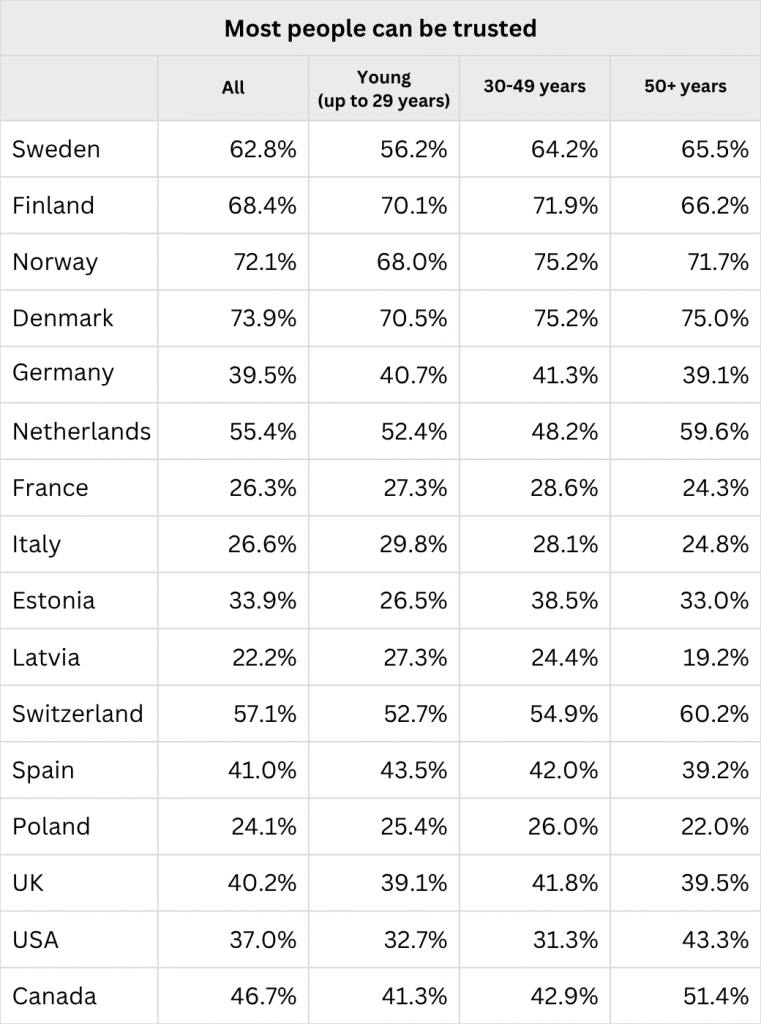

Sweden has high trust, but not to the same extent as the other Nordic countries. While in Denmark, Finland, and Norway, around 70% of young people believe that most people can be trusted, in Sweden, the corresponding proportion is 56.2%.

When looking at the overall population in Sweden, 62.8% agree that most people can be trusted. For comparison, the figures in Norway and Denmark are 72.1% and 73.9%, respectively. In Finland, 68.4% of adults hold this perspective.

The chicken or the egg?

Which came first in the Nordics: trust or the welfare state? Andreas Bergh and Christian Bjørnskov have employed several statistical techniques to investigate the potential connections between high trust and the Nordic welfare model. They concluded that trust predates the welfare state, so it does not seem that the growth of the welfare state is the primary factor in creating trust. Instead, it is more plausible that high trust has enabled high taxes and the development of the welfare state.

If it is true that the welfare state requires rather than creates trust, the recent development of norms is problematic.

The share of Swedes with high trust grew from the 1980s, peaking in the early 2000s. But since then, trust has declined. This pattern of decreased trust since sometime around 2010 is also evident in other high-tax countries.

Given that high trust is a prominent Nordic characteristic, it would be reasonable to suppose that Sweden’s lower figures are due to the significant immigration from non-Nordic countries. However, the study points out that the percentage of native Swedes who agree that most people can be trusted, 64.8%, is only marginally higher than the overall population. In comparison, 75.3% of native-born Danes express the same level of trust.

You’re clearly someone who enjoys staying ahead of the curve

Why stop now? Click here and join the TechTalents Insights community. Get bi-weekly trends and expert takes — free and delivered straight to your inbox.